By Anuradha Dutta

Nagaland, more popularly known as the “Land of Festivals,” is one of the most culturally rich and visually spectacular states of India, located in the country’s northeastern corner. It borders Assam to the west, Arunachal Pradesh and a portion of Assam to the north, Manipur to the south, and the international border of Myanmar to the east. Even though it is one of India’s lesser states in terms of area and population, Nagaland is incredibly diverse in culture, due to the existence of 16 officially recognized tribes, each of which has its own language, customs, dress, and special set of traditions.

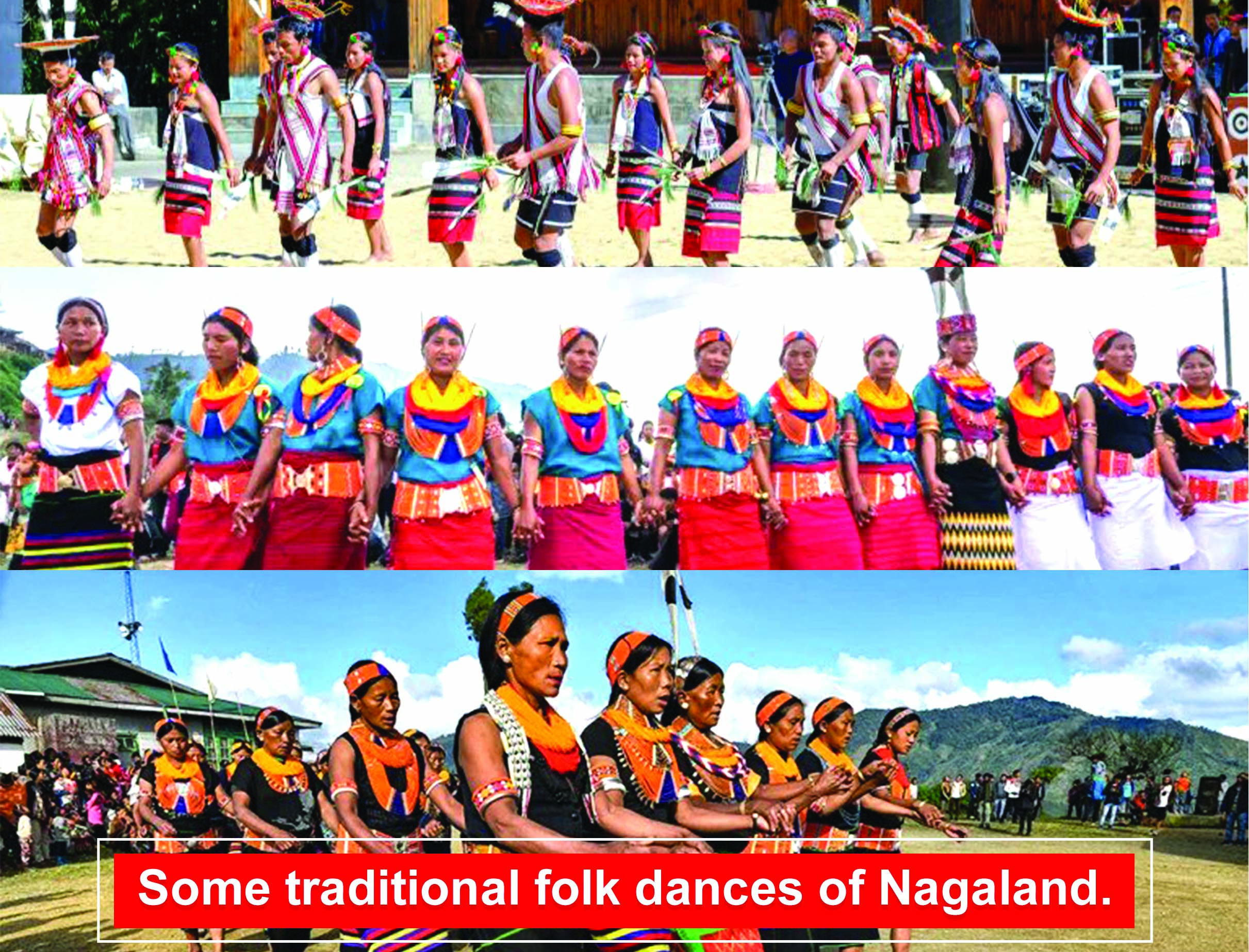

The country itself is a patchwork of rolling hills, dense forests, and misty mountains, with a climate varying from subtropical to temperate. Nagaland’s residents are famed for their resilience, affectionate hospitality, and strong community ties. Day-to-day living centers on tribal life with ancient traditions and customs passed from generation to generation. The most striking feature of Naga culture is its rich dance and music heritage, which has its roots deeply embedded in agriculture, war, festival, storytelling, and religious beliefs.

Each Nagaland tribe has its own festivals, most of which are related to the agricultural cycle — sowing, reaping, or seeking divine blessings for a bountiful harvest. These festivals are usually accompanied by ceremonial dress, traditional food and beverage, and lively folk dances performed in open grounds or village courtyards. Every dance is a tale — one of courage in combat, thanksgiving to the natural world, or merriment in communal bonds — with accompanying traditional music like log drums, gongs, flutes, and bamboo clappers.

Although modernization and globalization have reached several regions of Nagaland, its populace still remains intensely proud of its heritage. The Hornbill Festival, organized each December in Kohima, is an event where all the tribes gather and share their dances, songs, handicrafts, and cuisine on a common platform. This has not only served to retain Naga culture but also taken it to the rest of the world, welcoming tourists, scholars, and culture seekers from around the world.

In comprehending Nagaland, one has to go beyond maps and figures — and into its essence, best articulated by its dances, songs, festivals, and oral folklore. The folk dances of Nagaland are not mere performances — they are living repositories of the collective memory, identity, and spirit of the tribes.

Sekrenyi Dance : Angami Tribe :

The Angami are one of the prominent Nagaland tribes that mostly reside in the Kohima district. Famed for their warrior past, rice terracing, and accomplished woodwork, the Angami have maintained an extremely spiritual and ceremonial lifestyle. They are also famous for the Hornbill Festival and their immaculately crafted traditional clothing that consists of cane, feathers, and beads.

Folk Dance: The “Sekrenyi” dance, the most celebrated dance of Angami tribe, is danced on the occasion of the Sekrenyi festival in February, a purification ceremony. Men wearing traditional full-length outfits, with spears and shields, represent strength and solidarity in the dance. War chants are sung and there are rhythmic steps in ring formations.

Moatsu Festival Dance: Ao Tribe:

The Ao people live mostly in the Mokokchung district. They are renowned for their rich folklore, oral tradition, and intense clan systems. Their festivals attest to a deep rural way of life and veneration of ancient customs.

Folk Dance: The “Moatsu” dance of the festival is a core feature of Ao festivals, celebrated in May at the time of sowing seeds. The dancers move as lines with elegance, clapping and singing folk songs, conveying happiness, gratitude, and communal sentiment. Bamboo flutes and log drums are the instruments used to accompany the dance.

Tuluni Dance: Sumi Tribe:

The Sumi, otherwise referred to as Sema, reside in the Zunheboto district and in sections of Dimapur. Traditionally, they are referred to as fierce fighters and are characterized by their colorful shawls and lively musical culture.

Folk Dance: The Sumi dance the “Tuluni” dance in the Tuluni festival held in July, which is a festival of fertility and harvest. Both men and women dance, arranging themselves in semicircles and dancing to the beat of traditional drums and bamboo instruments. The dance also entails symbolic drinking from a shared rice beer container.

Tokhu Emong Festival Dance: Lotha Tribe:

The Lotha community resides in the Wokha district and is famous for its traditional system of governance, war and love songs, and a rich cultural heritage based on nature.

Folk Dance: Tokhu Emong festival showcases the most prominent of the Lotha dances. Dancers adorn headgear in a traditional manner and execute synchronized footwork while singing stories of historical victories, societal bonds, and thanksgiving. Log drums and bamboo percussion form the musical accompaniments.

Tsukhenye Dance : Chakhesang Tribe :

The Chakhesang tribe is constituted by uniting three sub-tribes: the Chokri, Khezha, and Sangtam. Found in the Phek district, they are known for their terraced agriculture, skilled craftsmanship, and bright clothes.

Folk Dance: At the “Tsukhenye” festival, the Chakhesang dances are performed during which cleansing, renewal, and blessings for the upcoming year are symbolized. The dances are slow and ritualistic and tend to be around a central fire with chanting and gongs.

Aoling Festival Dance: Konyak Tribe:

The Konyaks, found in Mon district, are maybe the most dramatically handsome tribe, being famous for facial tattoos, blackened teeth, and a fierce warrior tradition. They used to be head-hunters but now have developed into a tourist-and-heritage-conserving deeply involved tribe.

Folk Dance: Konyak dance, enacted during the Aoling festival in April, illustrates war preparation and celebration after war. Dancers adorn their heads with hornbill-feather headgear, boar tusks, and conventional ornaments and bear spears and rifles in their hands. Their steps are forceful, rhythmic, and supplemented by war warbles and drum-beats.

Monyu Festival Dance: Phom Tribe:

The Phom live in the Longleng district and have bamboo crafts, colourful shawls, and rich spiritual customs. Their tradition is heavily oriented towards agriculture and clan ceremonies.

Folk Dance: The “Monyu” festival is celebrated with dances of unity and rejuvenation. Men and women stand in a separate line and execute synchronized moves, representing harmony between nature, ancestors, and the current generation.

Mongmong Festival Dance: Sangtam Tribe:

The Sangtam people inhabit the Kiphire district and some area in Tuensang. Their tradition is characterized by ritualistic activities, millet farming, and bright beadwork.

Folk Dance: Ritual dances are performed when the “Mongmong” festival takes place, and they serve to bring good harvests and appease gods. The dances tend to replicate farm work and are performed to the beat of chants and gongs.

Metümnyo Festival Dance: Yimkhiung Tribe:

The Yimkhiung, or Yimchunger, tribe is largely concentrated in the Shamator and Kiphire districts. The Yimkhiungs have traditionally been associated with compact villages, strong animistic faith, and refined dress made of natural fibers and dyed with vegetable pigments. Their culture revolves around clan loyalties and traditional farming methods, especially jhum cultivation.

Folk Dance: The Metümnyo festival is the primary cultural celebration of the Yimkhiungs, celebrated in August. Folk dances are danced during the five-day festival to convey unity, love, and rebirth. Male dancers may carry symbolic weapons and women wear colorful shawls and do complex footwork. Log drums, chanting, and rhythmic clapping accompany the dances.

Miu festival Dance: Khiamniungan Tribe:

The Khiamniungan people live in the Noklak district and along the Indo-Myanmar border. Traditionally known for their warrior spirit and courage, the Khiamniungans were headhunters until the mid-20th century. Presently, they are famous for their wood carving, weaving, and colorful ceremonial attire with beads, bones, and feathers.

Folk Dance: The Miu festival in May is one of gratitude commemorating the onset of sowing time. Dances here reflect unity, farm success, and homage to ancestors. The dancers in most cases perform in broad circles, with foot-stomping and shoulder action, simulating collective cultivation. Bamboo flutes and war gongs play the traditional musical accompaniment.

Ngada Festival Dance: Rengma Tribe:

The Rengma tribe is mainly found in the Tseminyu district. They are one of the most culturally advanced tribes in Nagaland, recognized for their beautiful woodwork, distinctive traditional systems of governance, and complex rituals. Rengma people’s cultural heritage comprises ceremonial songs, clan totems, and sacred forest traditions.

Folk Dance: At the Ngada festival in November, ceremonial dances by the Rengma celebrate the successful end to the harvest season. Woven shawls and headdresses of cane and feathers are worn by dancers, gliding to slow drumbeats and bamboo pipes. The dances express thanksgiving and community affiliation.

Liangnyu Festival Dance: Zeliang Tribe :

The Zeliang tribe, a mix of Zeme and Liangmai sub-tribes, is predominantly located in the Peren district. They are farmers, forest people with a rich oral tradition and colorful folklore.

Folk Dance: The Liangnyu, the Zeliang’s traditional festival, features a breathtaking array of dances depicting tribal tales of migration, war, and fertility rituals. Men wield spears and shields in rhythm and women join circle formations of grace. Wooden rattles and rhythmic drumming are the chief instruments.

Yemshe Festival Dance : Pochury Tribe:

The Pochury people inhabit the Meluri area of Phek district. Their genesis is from a mixture of three ethnic subgroups, and they are characterized by their shamanic practices, sacred stone worship, and mystical folklore. The Pochurys are very religious, and most of their dances are symbolic with mythological and prophetic connotations.

Folk Dance: Yemshe festival in September is an occasion for purification and future benedictions. They perform both individual and group performances, dramatizing agricultural operations or spiritual pursuits. Performed along with chanting and conch blowing, it is one of the most spiritually uplifting performances of Nagaland.

Naknyulem Festival Dance : Chang Tribe:

The Chang tribe inhabits predominantly in Tuensang district and is famous for their simplicity in living, bamboo dwelling, and colorful dances that usually resemble birds and animals. They are traditionally hunters and farmers, and the Chang people give a lot of importance to clan solidarity and oral knowledge transmitted over generations.

Folk Dance: Chang dancers dance with abandon during the Naknyulem festival in July. The dances usually start with rhythmic stamping, followed by clapping in unison, chanting, and dramatic displays of love, harmony, and farm themes. Women adorn themselves with layered jewelry and black skirts, while men wield ceremonial daos (machetes) and shields.

The Nagaland folk dances are not just an entertainment, but an intense reflection of the rich cultural fabric created by its various tribes. Every dance is a narrative — be it one of agrarian thanksgiving, warlike courage, community cohesion, or worship of the divine. By these dances, the Nagaland tribes keep their history alive, transmit ancestral wisdom, and keep their distinctive traditions alive.

From the dynamic and energetic steps of the Angami tribe’s Sekrenyi dance to the religious symbolism of the Pochury tribe’s Yemshe festival, every performance is a testament to the strong bond between the people and their land. The dances are living repositories of Nagaland’s identity, capturing the changing dynamics of a society that, though adopting modernity, remains firmly grounded in its heritage.

As Nagaland keeps twinkling globally with such festivals as the Hornbill Festival, these folk dances continue to remain at the center of the cultural pride of the state, depicting resilience, solidarity, and shared heritage. The Nagaland folk dances are not performances only — they are reflections of life itself, cutting across generations, and conserving the essence of the land for future generations to watch and marvel at. rr

References:

1. https://nagalandgk.com/traditional-folk-dances-of-nagaland/

2. https://oddessemania.in/nagaland-dance/

3. https://www.culturopedia.com/folk-dances-of-nagaland/

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nagaland

5. https://nagaland.gov.in/pages/people-culture

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nagaland

7. https://www.sentinelassam.com/north-east-india-news/sikkim-news/lets-know-more-about-the-traditional-dance-of-nagaland